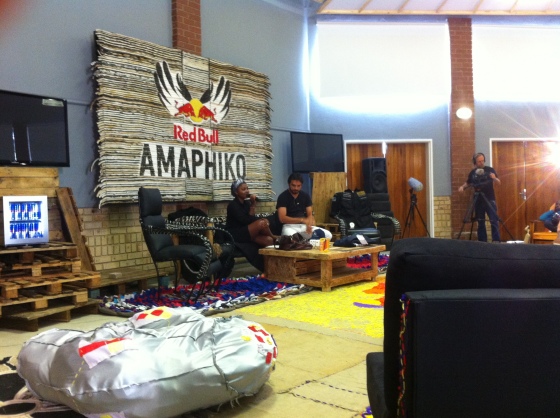

Earlier this month I travelled to Soweto for the inaugural Amaphiko Academy. It’s a ten day academy for social entrepreneurs, put together by Red Bull.

Eighteen South African social innovators were selected to take part. Some of them were running pretty sophisticated social enterprise, others had never heard the words ‘social’ and ‘enterprise’ put together and certainly didn’t know that their after-school art project or skate education scheme or township gardening operation was indeed a social enterprise.

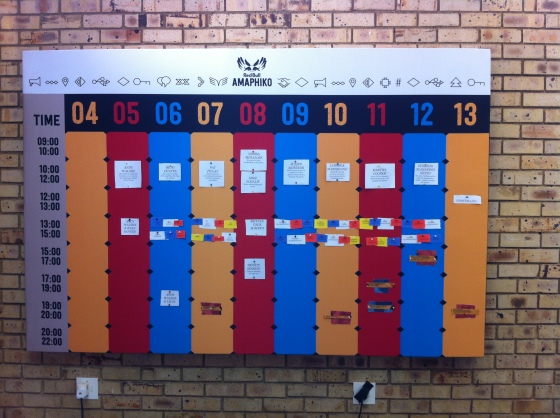

It was eye-opening for everyone. Each day comprised a moderated lecture (hence my involvement) with a top-flight guest, ranging from MIT’s entrepreneur-in-residence Julius Akinyemi, to Subway Art photographer Martha Cooper to Andy Walshe, director of high performance at Red Bull. The afternoons were spent in small crowdfunding workshops or in sessions where participants could co-create a logo or a short video, or where they could just work out ways of explaining exactly what they do.

Soweto is a huge place (population 1.5m) and much of the world’s most famous township is in pretty good shape. There’s a growing tourist industry, a new theatre and one of SA’s largest shopping malls. Some of Soweto, though, is still grindingly poor, like Kliptown, the area just across the tracks from our hotel where Amaphiko staged three evening events – itself a small, trusting, leap from the usual way of doing things. There’s nothing quite like walking along train tracks in the dark, with burning tyres as street lighting, chaperoned by street kids in youth centre t-shirts, to challenge your preconceptions.

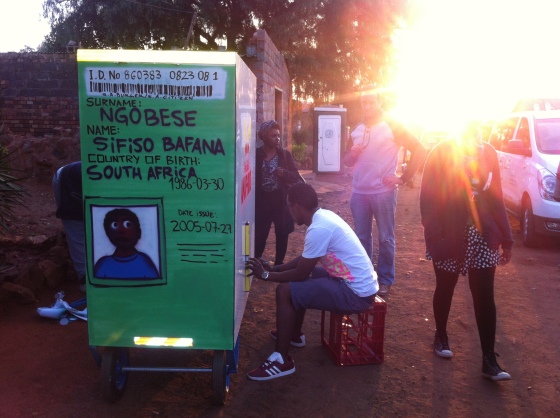

I saw a huge degree of civic duty, innovative thinking and low-resource ingenuity. Meshack Sitoe runs an arts project for people with learning difficulties where they don’t have money for clay – so collect it from the riverbed. When his project was kicked out of their community centre he dusted himself off and set up in a friend’s back yard. Ramona Kasavan realised that girls were missing over 300 days of schooling a year because they couldn’t afford proper sanitation during their periods – and developed a two-pronged solution that involves a low-cost, high-performance pad and the rebranding of periods as ‘happy days’. Sifiso Ngobese realised that the township reclaimers who lug hug loads of rubbish each day to recycling for pittance wages were actually doing a great civic service – and developed branded, durable carts that both make life easier and rebrand these workers as heroes, not lowlife.

This resourcefulness was also present in the people we met along the way, like the Kliptonians who run the SKY Youth Centre, or the collective of artists behind the Post 77 Gallery, or the kids adapting reclaimed plastic toy trucks with a long stick to make them more navigable. In a world where low-resource ingenuity will become more valuable as resources become increasingly scarce, societies like Soweto are well-placed to thrive – and there’s a lot we can learn from them.

It’s increasingly obvious, to quote Peter Senge in this month’s RSA Fellowship Magazine, “we’re not going to be able to keep privatising profit and socialising cost to the degree we have been.” Projects giving grass-roots social entrepreneurs access to networks and opportunities are a good start. It’s about putting social profit on a par with financial profit and recognising the value that both bring.

I don’t feel I got to know too much about the vastness of South Africa in my short stay, but I feel like I got a strong taste of Soweto, a place described in Philip Bonner and Lauren Segal’s excellent ‘Soweto: A History’ as “a catalyst… what happens in Soweto will determine what happens in the whole country.” On the 20th anniversary of democracy in that country, here’s to a new generation of social upstarts. And the next Amaphiko academy. I’m in.

08

Jun

Exiting the news purdah

A month ago today I saw the exit poll results and turned the news off. I haven’t turned it on again.

I’d embarked on an unplanned news black out. I stopped watching TV and I avoided Question Time, which is really just a middle class version of Jeremy Kyle anyway. I stopped listening to the radio, apart from Radio 3, which only has news once an hour and pirate radio, which has news never.

What’s done was done and it was going to be bad for anyone unlucky enough to be poor or incapable. There was nothing I could do about it, so I switched off.

Social media was also off the agenda, because I knew that most people I knew would be raging into the echo chamber of Facebook and Twitter and that felt disheartening and pointless. I averted my eyes from free newspapers when I was working in town and avoided conversations about politics.

Some news filtered through early, mostly from the far-off land of my teenage son, but mostly I spent the last month vacuum-packed, protected from unsightly post-result posturing and jostling. I only found out Michael Gove was Justice Secretary last week and immediately wished I hadn’t.

My news blackout posed an interesting question: what happens when you’re not being enraged and distracted by the minutia of the daily news grid?

The answer is that unsurprisingly, it gives you back a lot of time. It also focuses the mind on what you can do rather than what you can’t. Cabinet ministers waft into the distance when you don’t see them every day, remote and shapeless as smoke, and local problems pop into focus in their place.

The last month of national radio silence has made me want to connect locally. The main thing now is rediscovering our individual and collective impulse to do it ourselves, to find opportunities to volunteer, and to strengthen ties with the communities we’re already part of through location or background or interests. We need to make alliances outside of our usual friends and family. And then, who knows what might emerge?

We don’t have the same collective impulse as Spain, which makes it harder for a phenomenon like Podemos to occur, but we do have a long-established tradition of DIY culture. If the mainstream isn’t providing, we’ve filled the gap with grassroots responses, whether that’s pirate radio or punk. We’ve also, thanks to a useful bit of local democracy, now got new neighbourhood forums that give communities legal rights and powers to shape new developments.

So that’s what I’m saying: DIY and do it local – and don’t let the news distract you.

Image: Jon S

Share this:

9 years ago Short URL Comments

social commentary/Uncategorized

a month on from the election/DIY/election/election result/national politics/neighbourhood forums/news/Pirate Radio/podemos/punk/purdah